Born in Durham on February 21, 1902, the daughter of G. H. Leatham and his wife Edith (nee Rutter), and educated at Durham High School for Girls, before finishing at Le Manoir in Lausanne on the shores of Lake Geneva. She obtained her BA in English Literature in 1926 at the University of Durham where she also met her future husband, a clergyman, V. R. Hill. They married in Newcastle in 1928 and had one daughter, Shirley Victorine (known as Vicki).

In 1932, the family moved to Matfen, Northumberland, and Hill settled down to the life of a country vicar’s wife. ‘Looney’ Lorna (a nickname she earned because of her strange atire, chosen by her poetic mother) had begun writing and illustrating her own stories at around the age of 12—often at school when she should have been studying math or Latin—using them to barter with her school friends for toffee apples. These old exercise books were discovered by Hill’s 10-year-old daughter many years later and, after reading one, the young girl wished that there were more.

With money scarce due to the war, Hill sat in front of her kitchen fire and wrote Marjorie & Co. which delighted both Vicki and her school friends when it was given to her as a Christmas present. Over the next few years, Hill continued to write for her daughter’s birthdays and Christmas without thinking of publication.

A visitor to the family also happened to be a publishers’ reader and he recommended she sent her books to an agent. The first, written in longhand in an old 1/9d stiff-backed notebook, was sold to the Glasgow firm of Art & Educational Publishers who published it in August 1948, replacing Hill’s watercolour illustrations with artwork by Gilbert Dunlop. The company asked to see more, and Hill—who had by now taught herself to type, albeit only with two fingers—sent them a number of other manuscripts which were all accepted. However, only two further novels were published before Art & Educational ceased trading.

The London-based Evans Bros. began publishing her Sadler’s Wells books, written after Vicki had decided to become a dancer following a family visit to see Alicia Markova and Anton Dolin at Newcastle’s Theatre Royal. Although inspired by her own daughter’s desire to become a dance student, the new series featured an orphan who secretly practices so she can audition for the ballet school. Angela Bull, in 20th Century Children’s Writers has called A Dream of Sadler’s Wells “a wish fulfilment story about Veronica Watson, a child dancer, recently orphaned, who is sent to live with some rich, snobbish relations in Northumberland.

Here, besides riding and enjoying a romantic friendship with a boy musician, she secretly practices her dancing, until, in the end, she auditions for Sadler’s Wells Ballet School and is accepted as a student. A Dream of Sadler’s Wells was the first of a long series of inter-locking ‘Wells’ novels, following Veronica’s entirely predictable progress through the ballet school to starring roles at Covent Garden and marriage with the young musician, while at the same time widening out to include the dancing careers of other talented orphans, or daughters of Northumbrian county families.”

Bull’s assessment that the series “soon drowns in syrupy romance” was not shared by Hill’s world-wide readership, who went on buying the books for over a decade. The books were still being reprinted in the 1990s.

Hill added series’ featuring Patience, written for Burke, and the Dancing Peel books published by Thomas Nelson, but the time of prolific publishing for the children’s market came to an end in the mid-1960s and apart from an invitation to write a biography of dancer Marie Taglioni, she did not write again until the late 1970s when she wrote two adult romance novels.

At the height of her fame, Hill was also heavily involved in animal rights and the removal of gin traps from the local fields after one of her cats had to have a leg amputated. Throwing them into the river when she found them, she was summoned to Court and ordered to pay compensation. In response, she refused to pay; instead, she rented the rabbiting rights to the field herself to protect the animals and organised an animal welfare service on Matfen village green which one year attracted over 500 cars in support. In 1954, she turned her attention to fur coats.

Hill later lived in Keswick, Cumbria, where she died on August 17, 1991, aged 89.

Although many of her Sadler’s Wells were reprinted in the mid-1980s, most of the fondly-remembered Marjorie and Patience stories were long out of print. Fans visiting Hill’s daughter in 1997 discovered that one of the exercise books in which her early stories were written contained a previously unpublished novel, Northern Lights. It had been rejected for publication because the story, written in 1941, involved the war. The book finally saw print in 1999 and the same publisher, Girls Gone By Publishing, has subsequently reprinted a number of other rare Hill titles.

Hill’s daughter, Vicki, had submitted sample illustrations to Art & Educational but, to avoid any bias, used the pen-name Esmé Verity. When Border Peel appeared, Hill phoned her daughter in Manchester and told her how delighted she was with the new illustrator who, co-incidentally, must be a neighbour. When she discovered who the artist was, the two continued the joke by inviting their publisher to meet the artist for lunch.

Publications

Novels (series: Dancing Peel; Marjorie; Patience; Sadler’s Wells; The Vicarage Children)

Marjorie & Co. (Marjorie), illus. Gilbert Dunlop. London & Glasgow, Art & Educational, 1948.

Stolen Holiday (Marjorie), illus. Gilbert Dunlop. London & Glasgow, Art & Educational, 1948.

Border Peel (Marjorie), illus. Esmé Verity. London & Glasgow, Art & Educational, 1950.

A Dream of Sadler’s Wells (Wells), illus. Eve Guthrie. London, Evans Bros., 1950; New York, Holt, 1955.

Veronica at the Wells (Wells), illus. Eve Guthrie. London, Evans Bros., 1951; as Veronica at Sadler’s Wells, New York, Holt, 1954.

They Called Her Patience (Patience), illus. Gilbert Dunlop. London, Burke, 1951.

Masquerade at the Wells (Wells), illus. Eve Guthrie. London, Evans Bros., 1952; as Masquerade at the Ballet, New York, Holt, 1957.

It Was All Through Patience (Patience), illus. Gilbert Dunlop. London, Burke, 1952.

No Castanets at the Wells (Wells), illus. Eve Guthrie. London, Evans Bros., 1953; as Castanets for Caroline, New York, Holt, 1956.

Jane Leaves the Wells (Wells), illus. Eve Guthrie. London, Evans Bros., 1953.

Castle in Northumbria (Marjorie), illus. Gilbert Dunlop. London, Burke, 1953.

Ella at the Wells (Wells), illus. Eve Guthrie. London, Evans Bros., 1954.

Dancing Peel (Peel), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1954.

So Guy Came Too (Patience), illus. Joanna Curzon. London, Burke, 1954.

Return to the Wells (Wells), illus. Eve Guthrie. London, Evans Bros., 1955.

Dancer’s Luck (Peel), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1955.

The Five Shilling Holiday (Patience), illus. Joanna Curzon. London, Burke, 1955.

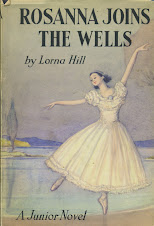

Rosanna Joins the Wells (Wells), illus. Eve Guthrie. London, Evans Bros., 1956.

The Little Dancer (Peel), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1956; New York, Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1957.

Principal Role (Wells), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Evans Bros., 1957.

Swan Feather (Wells), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Evans Bros., 1958.

Dancer in the Wings (Peel), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Evans Bros., 1959.

Dress-Rehearsal (Wells), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Evans Bros., 1959.

Back-Stage (Wells), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Evans Bros., 1960.

Dancer in Danger (Peel), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1960.

The Vicarage Children (Vicarage Children), illus. Marcia Lane Foster. London, Evans Bros., 1961.

Vicki in Venice (Wells), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Evans Bros., 1962.

Dancer on Holiday (Peel), illus. Esmé Verity. London, Nelson, 1962.

No Medals for Guy (Marjorie), illus. Gilbert Dunlop. London, Nelson, 1962.

More About Mandy (Vicarage Children), illus. Ann Kent Robinson. London, Evans Bros., 1963.

The Secret, illus. Esmé Verity. London, Evans Bros., 1964.

The Vicarage Children in Skye (Vicarage Children), illus. Elizabeth Grant. London, Evans Bros., 1966.

The Other Miss Perkin. London, Hale, 1978.

The Scent of Rosemary. London, Hale, 1978; New York, Pinnacle, 1980.

Northern Lights. Bath, Somerset, Girls Gone By Publishers, 1999.

Omnibus

A Dream of Sadler’s Wells. Veronica at the Wells. London, Piper, 1994.

Non-fiction

La Sylphide: The Life of Marie Taglioni. London, Evans Bros., 1967.

Lorna Hill Portrait

Wednesday, 15 April 2009

The Trouble with Guy

Guy Charlton

A Hero Lost and a Hero Found

by

Philippa Morley

“Hurrah!” I shouted in the best pony story fashion. “This is simply the most super news I’ve heard in years.”

My husband retreated further behind his newspaper as though he could hide from the wonderful discovery I’d just come across in Charlotte’s letter. Somehow he thinks that The Times and a stoical silence will keep me from telling him even the most vital snippets of information.

“They’re reprinting the ‘Marjorie’ and ‘Patience’ stories by Lorna Hill. I’ll be able to collect them and read them all over again.”

Silence.

“Did you hear, Edward. They’re reprinting Lorna Hill’s stories. You remember how upset I was when I learned mother had given them all away to a jumble sale whilst we were out in Hong Kong.”

“Really, dear, that’s very nice.”

Honestly, what did I expect after 35 years of marriage? Something more than “nice” I suppose. The more I thought about it, the more I realised that I wanted more from him than I could reasonably hope to receive. The problem was that Edward just wasn’t like Guy. All my life I had been hoping to meet someone like Guy.

Guy? Guy Charlton, of course—the clear hero of the ‘Marjorie’ books and sometimes hero of the ‘Patience’ stories. Why Guy was indispensable to me when I was growing up in Newcastle Upon Tyne in the 1950s and 1960s! You see I expected to meet him around every corner. I would be walking down from the girls’ Central High School and he would be in town from Horden Castle and we would bump into each other at the top of Northumberland Street, just where it turns into the Haymarket. My parcels (why I was carrying parcels I can never explain) would fall to the floor and he would rescue me, apologising even though it had mostly been my fault. And that would be the start.

Pretty soon I would be on holiday with him and the others in the depths of the Northumberland countryside or on some remote beach near Bamburgh Castle. I conveniently ignored the fact that Lorna Hill had decided on a very different destiny for her favourite young man and had myself married off to him. I can vividly remember riding down an avenue of tall trees lined by all the characters from the books with swords upraised over our heads in salute, as our carriage, driven by Guy himself with masterly control, headed off into the sunset. My favourite pony, Border Thunderer, would be waiting in Horden Castle for us to get back from our honeymoon…

Well, I married Edward instead and spent thirty years staring at the outside pages of The Times across the breakfast table.

But, enough of that.

Charlotte’s letter had made me determined to revisit the stories of my youth and meet again the object of my schoolgirl dreams and desires. It would take too much patience to wait for the whole series to be reprinted. Now that the idea was in my mind I had to have the books.

Well, I had no idea that they would prove so difficult to obtain! Just one turned up in a second-hand book-shop in my local area. A friend persuaded me to go on the Internet and by paying through the nose, I managed to collect a further six volumes, some with dust-covers and some without. I could have had any number of ‘Sadler’s Wells’ stories but my friend, Lucy, has a full collection of those and I knew I could borrow any of the fourteen ballet stories, plus a few ‘Dancer’ adventures if I really got the Lorna Hill bug.

With some trepidation, therefore, forty years later, I opened the copy of Marjorie and Co. and began to read. This, I suppose, is where this article really starts and so I apologise for all the waffle so far. However, these books had meant such a lot to me and I feel you need to know that I am not exactly a detached critic when I make the observations which follow.

I don’t know about you but when I was reading books as a young girl and as a teenager I used to skip the little introductions and the ‘forewords’ and ‘prefaces’. “Just get on with the story” was my motto. A lifetime of scanning the small print and sad experiences with missing vital instructions on household appliances has taught me to be a little more patient and circumspect. Now I read everything. And so I read the Foreword to Marjorie and Co. and that’s when I received my first shock. Writing in the first person character of Pan, Lorna Hill actually opens the first book by describing the faults of each of the characters.

“Guy is distinctly bossy, Toby is what the grown-ups would call ‘a bit on the stolid side,’ Esme hasn’t the ghost of a sense of humour, whilst I’ve got oceans of faults.”

So “Guy is distinctly bossy”. Well, that’s just Pan’s opinion, isn’t it? Obviously one of her “oceans of faults” is the inability to see Guy as he really is. Honestly, you would think she would know better than to criticise him for one of his virtues. I mean Guy is just so masterful. There’s nothing namby-pamby about him. As for those girls, I had never understood what he could see in them. But, even as these thoughts were crossing my mind, I realised that I was being unfair. Then, as a twelve year old girl, Pan, Esme and Marjorie had been like rivals for the hand of my hero—now I have seen my first grandchild arrive in the world, and I gaze at life from the wrong side of fifty, I really ought to know a little better. After my first ‘new’ reading of Marjorie and Co. my thoughts had undergone a glorious revolution that I should like to share with you. The tiresome girls that got between me and the lovely Guy were transformed into my best friends and, as I began to understand with mounting appreciation, that they were, in fact, reflections of different aspects of my own character. It was in fact the ‘hidden me’ that I had never wanted to acknowledge, those uncertain thoughts and feelings that eventually shape us into the people we become. More marvellous even than the people were the countryside and the towns where all the stories were set—in those days they were simply “the places where exciting things happened.” Now they are my only route to the past, unless I accept the challenge of writing a very dull autobiography of my early years in the North-East. Even then I still wouldn’t have the gift of a Lorna Hill.

As early as the first chapter of the first book I began to get these feelings. Poor Esme and Pan have to make a “courtesy visit” to have tea with Marjorie Manners, a girl who lives in their neighbourhood but who also goes to their boarding school. They already know her well and heartily dislike her. Back then what parents said was law. Pan tries every argument she can think of but is met with her mother’s implacable resolve:

“Well, I’m afraid you’ll have to go and have tea with her,” insisted Mummy firmly, cutting me short.

Oh, those “visits”—with what pain I can still remember them! Mine were mostly to elderly relations in other districts of respectable surburbia in Newcastle. They normally took place on a Sunday and only those that have lived through the dullness and oppression of spirit caused by a 1950s Sunday afternoon and evening can fully appreciate the depth of my feelings.

However, let us be fair. The first chapter of Marjorie and Co. makes it clear that children both then and now seem to have that specially programmed capacity to wreak a peculiar form of revenge for being brought into the world in the first place. As Pan and Esme beg and beg for ponies to ride and fill every letter home from school with unceasing ‘horsy’ information, so I am reminded of my marathon nagging sessions which eventually reduced my mother to frustrated acquiescence in my latest fad. Yes, let us try to dispense justice to both sides in the never-ending war between the generations. As I look back to the freedom enjoyed by the girls in this story with the benefit of thirty odd years hindsight I realise that they and I were living in a literary ‘make believe’ land. However, whilst the implausibility of several of the plots now makes itself clearly apparent, I can recognise a deeper truth in some of the behaviour that I never noticed before.

Take Marjorie, for instance. She is meant to be the villain of the piece and we can soon understand the dread that fills Esme and Pan as they draw near to Windynooks, the Manners’ opulent house. However, we are not treated to Marjorie ‘swanking’ over the tea-table whilst Pan and Esme feel like poor relations. That’s much too tame for Marjorie.

Marjorie never arrived decently—she always burst, or sprang, or flung herself. She was riding bareback, and I suppose she did look rather striking in her jodphurs and scarlet sweater—she often wore scarlet. I think she knew that it suited her dark prettiness—not to mention her disposition!

I ask you honestly, “Who would you rather be—Esme tumbled in an undignified manner into a holly bush, Pan sitting bolt-upright on her little cart-house of a pony or Marjorie arriving with dramatic effect and admired by her contemporaries for her attractive appearance?”

However, neither Pan nor Esme is lacking in spirit and they show this on the first encounter. As Marjorie shows off her new swivel manger and declares “No fear of flashing heels and snapping teeth,” Esme traces the smart remark to an advertisement in Horse and Hound and says she thinks the manger would be jolly useful for pigs. Pan manages to get in her own deflationary remark about new saddles being so stiff and horrid. The chapter ends with Pan confessing that “Really, Marjorie brings out all the worst in me!”

All her carefully cultivated attempts at politeness to her hostess have been forgotten but, nowadays, I soon recognised that, of course, Marjorie has been put into the stories to bring the best out of everybody and this includes my lovely Guy.

Chapter Two is a catalogue of Marjorie’s sins. She really does behave appallingly. In a race with Esme she sets off before the word “Go” and later hits poor Willow with her riding crop just in case there was a chance of being beaten by a rival mount. Naturally Willow, with an inexperienced rider, sets off at a frantic speed towards a nearby wall. Disaster lies ahead for Esme. It’s time for the hero to make his presence known. Like Marjorie, Guy can never arrive tamely on the scene and he performs the fairy-tale prince act with skill and panache. Already Esme has lost her heart to him and Marjorie is ready to take him on as a serious opponent. Everything she tries, including further cheating and attempts to hit him with a riding crop, is doomed to failure in the face of his imperturbable will. I used to relish his victory in this first encounter but now I am not so sure. It comes a little too easily and is a little too absolute. Black and white is no longer so attractive to me in literature as the more subtle shades of grey. However, Lorna Hill doesn’t let me down and I read with astonishment a passage that had entirely eluded my memory. Yes, yes—I had taken in the information before but I had never really followed the flow of the narrator’s emotions so closely. It concerns Pan and how she came to get her name:

“You see,” I went on, determined to get it all off my chest, “it was a filthy woman—I mean a mouldy woman, a poetical friend of Mummy’s when Peter and I were born. Peter’s my twin brother, by the way. She—the woman, I mean—raved like everything about Peter Pan, and got Mummy to call us that? One Peter and the other Pan-sy. Awful, wasn’t it? Of course Peter was all right, but there was I, dubbed Pansy for evermore!”

For Pan it is a cruel joke that she doesn’t look like anything that could have the remotest claim to beauty and certainly not a flower “unless it’s a spotted orchid, or something that’s got freckles! I’m not even a common or garden dandelion.”

No amount of kind words from Esme or gruff common sense from Guy can take the edge off this sad confession of the lack of self-worth that Pan feels about herself. And that’s what cut me to the heart, for, much as I had always wanted to be the sweet and pretty Esme or the lively and spirited Marjorie, I realise now I was in fact more often the faltering and miserable Pan.

So, as I read all the ‘Marjorie’ books that I could lay my hands on for the first time in donkeys’ years, I began to develop an extra special relationship with this least likely of heroines. After all she was a splendid comic narrator and her frustrations with the inadequacies of the English language caught exactly my own feelings about the way in which words have to be carefully watched or they take on a life of their own. Take, for instance, that day that she discovers Otis Island. Pan is left on her own and begins to explain why her friends are not available. She reaches Esme:

Esme had been hauled off to the dentist’s, so she was a dead loss, because nobody, however hard they try, can concentrate on anything but the job in hand—I should say the job in the mouth!—when they are at the dentists!

Best friend or not, on the same day Esme comes in for her fair share of teasing. We can appreciate again Pan’s way with words and the choice of the apt simile:

“Well, now, can we have our council of war?” asked Esme in an injured tone. “You do make a fuss about unimportant things!”

Guy turned and looked at her sternly.

“Another word from you, my child, and I’ll—I’ll—I’m dashed if I know what I’ll do to you.”

“Wash the tidemark off her neck!” I suggested wickedly.

Poor Esme flushed crimson.

“Pan! Don’t be hateful!”

“Well, you know you have one—a huge one! It’s like Roker sands on a Saturday night, after the trippers have gone home... Ouch! Let me go, you beast!”

The attack on Pan comes from Guy and he tells her off for making personal remarks. It’s funny that I hadn’t noticed quite how often he steps in to be protective towards Esme. He enjoys teasing her himself but he won’t let anyone else do it. Yet, as I read Pan’s splendid description of her journey down the river after Miss Otis, her mischievous cat, and saw how she faced up to Guy and his anger, I began to feel more and more sympathy with the girl that I had always regarded as the nonentity of the group.

Gosh, isn’t Marjorie awful? I had forgotten at least two thirds of the things she did. Who could like a girl who cheats in races, makes constant sneering remarks, burns their gymkhana fences, saws holes in the bottom of their boat, covers their horses with tar and sprinkles their picnic sandwiches with paraffin? How could they let a girl like Marjorie into the clan that they had formed. The first time I read the book I couldn’t believe it. I remember thinking how noble it was of Guy to change his mind and to let her join. Here’s the key moment:

Then suddenly he changed the subject abruptly, and looked Marjorie straight between the eyes: “Why don’t you try being decent?” he asked her. “You could, if you set your mind to it. You’ve got loads of ‘go’ and pluck, and as for determination—whew!” He whistled.

I know that I ought to have appreciated this as a genuine example of Christianity, the parable of the lost sheep brought into the fold, but I was probably too busy simpering over Guy whilst at the same time thinking how lively the story could now become. This time through I was struck by Pan’s shrewd observation “…I, for one, had grave doubts as to the wisdom of Guy’s idea of admitting Marjorie into the Clan. He still didn’t know her as well as I did.”

Well, of course, Pan is right and Guy is wrong. It’s all very well thinking of those who go astray but Marjorie proves to be totally incorrigible. Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t have her any other way—the stories demand that she must be so. It’s just that the wisdom I have gained along with my grey hairs tells me that it’s not right that she should be allowed to cause such mayhem and suffering. When I think of what she does to Esme…

But back to Guy. Once I used to admire how grown-up he was and wonder how he could put up with the others so less experienced and less talented than himself. Now I feel like I am going through the books with a “smug” detector and finding that it is constantly setting off alarms:

“Gosh! You are a lot of kids, aren’t you?” he exclaimed. “I’m such a lot older—”

“Kids!” Marjorie retorted. “We’re nearly as old as you, let me tell you!”

“Not quite! I’m nearly fifteen,” laughed Guy. “Anyway, I didn’t mean in years; I meant in experience. So far, you’ve never done anything in your lives but play. Always some grown-up or other at the back, putting up picnic things for you, slicing the bread for fear you cut your fingers, giving you milk in a bottle, tea in a thermos – making things easy for you. I’ll bet you’ve never slept outside….”

But he is kind and, even in the first book, it is not just to the pretty and tender-hearted Esme. When Pan learns that her pony Billy is likely to be sold it is Guy that forces the truth out of her. It would have been so much easier for him to have treated her like the silly girl she was when she tried to overfeed the poor animal, and to have walked away from the disturbing outflow of feminine emotion.

Yes, he is as firm as a rock when it comes to any trouble but he is also disturbingly rigid when it comes to controlling the girls’ behaviour. I mean they are not really allowed to think for themselves and I sometimes believe it would be possible to accuse him of having double-standards. Take what happens at the circus. Marjorie seizes the opportunity to take part in a talent competition and wins half-crown. Guy is furious and hands back the money to the ringmaster. Later he attempts to tell her off:

“You only made yourself cheap tonight, Marjorie. You should have heard what the lads behind us were saying about you!”

“What were they saying?” Marjorie demanded eagerly.

“Never mind,” answered Guy severely.

“Oh, you’re old-fashioned—starchy!”

“Perhaps I am old-fashioned,” he admitted. “Anyway, those are my views. Take them or leave them!”

“I’ll leave them, then!” Marjorie said pertly.

“No, you won’t! You’ll jolly well take them, while I’m in charge of you.”

He insists that she scrub herself clean with carbolic soap so that Esme and Pan will not catch anything from the dirty sawdust and the soiled costume she wore. Then he calmly informs them all that he is taking part in the circus the following night in order to pay for the mistreated monkey that has caught Esme’s sympathy. At once Marjorie is there:

Suddenly there was a terrific whiff of carbolic, and Marjorie sprang into out midst, her eyes sparkling.

“Now who’s making exhibitions. Now who’s making himself cheap?”

“I’m not a girl, my good kid!” said Guy indignantly. “Anyway, I’m not just showing off. At least I’m doing it for a purpose.”

It’s just no good. Whatever his purpose, those first words “I’m not a girl...” make the hackles rise. I can tell myself with conviction that it is not hypocrisy on Guy’s part, that he genuinely believes that girls must behave differently, according to his pre-set ideas, but I still don’t like his certainty about his own rightness. I like him better some pages later when Pan realises that he has lost his temper with Claudine, the obnoxious little girl who has run away to their camp. I am even happier when I discover that the reason for his uncharacteristic loss of his temper is his affection for Esme. She has been slapped in the face by Claudine but has refused to sneak on her. Yes, as I read the books again I became quite reconciled to the fact that Guy’s affection for Esme considerably outdistanced his feelings towards anyone else. That’s what made it all the more upsetting when … But I’m getting ahead of myself, as Pan would say in one of her narratives, for I want to look next at Stolen Holiday.

Ah, Northumberland! If you have never been there, then you must go. It used to thrill me when I realised that I had been born in the same county as my hero. Even years later I used to ask my mother whether we had any relations who belonged to the Charlton family—no, not the illustrious footballing brothers who came from Ashington to represent England in our tremendous victory in the football World Cup. It was the wild borderers of the Middle Marches that I wanted to find amongst my distant kinfolk. The kinship must be distant, you realise, there must be no bar to our eventual nuptials. A girl can dream, can’t she?

You must go to Bamburgh Castle. Only then can you appreciate what Guy says as the superb Stolen Holiday begins:

Guy broke the silence.

“It’s queer,” he said slowly, “how this place gets hold of you! I’ve lived in Canada all my life, yet somehow it never seemed home like this does.”

Now I realise how clever Lorna Hill was in the way she created the background of her leading man. That Canadian upbringing gave her a rich vein of interesting differences for her to tap into as she developed more and more stories. Every aspect of the outdoor life was shown to be well within his compass. He can ride, he can swim, he can handle a boat, he can climb, he can run a camp—and he can do all of these things much better than his English contemporaries. He is tall, he is tanned and the contrast between his grey eyes and his dark hair makes him look even more striking. Moreover his manners are distinctly un-English. He has lived amongst French Canadians and not for him is the standoffish reserve of the English schoolboy of fifteen. Pan contrasts the shyness of Esme, Marjorie and herself with Guy’s lack of inhibitions.

We were all a bit shy, I think. Esme was distinctly pink, but Guy himself was perfectly natural and self-possessed. He swung Esme right off her feet and kissed her—he hadn’t nearly the same aversion towards kissing that we had.

What I would have given to be a member of the Clan at that moment waiting in turn to be greeted. But then I remember that he is really a bit of a dictator and will brook no arguments with his leadership. For him right is right and wrong is wrong and girls will not be allowed to behave badly and escape punishment just because they are girls. But should he be allowed to smack any of them—even the ghastly Marjorie? Really, it’s no good wondering whether he is right or wrong to do this, Guy will behave according to his interpretation of morality whatever I say or think. That is a part of the problem I now find with Guy. Surely it must be impossible to live with someone who is always right. It’s even worse being with someone who lets no error pass unchallenged. There’s always a time for keeping quiet, for letting people grow into a realisation of their own errors. And, anyway, is he always right? Let’s take the issue of teenage girls wearing make-up, for example. Naturally, it’s Marjorie who puts Guy to the test—who else would it be?

When she came out on to the veranda I thought there was something different about her, but I couldn’t think for the moment what it was. She looked extraordinarily pretty; her cheeks glowed, her eyes seemed even bigger and more melting than ever, her eyelashes were positively sweeping.

Guy is certainly entitled to his opinion and by now we know for sure that he is going to express it:

“Made-up?” he said contemptuously. “I thought that in England, at least, I wouldn’t see kids of thirteen with painted faces! You were quite a decent-looking girl before you put on all that filthy stuff. Now you look fit for nothing but a circus! Go and wash it off at once!”

Do you think he should have scrubbed her face with sponge and carbolic soap? Do you honestly believe he should have used Vim! I mean, have you felt Vim on your skin?

Just because it is the obnoxious Marjorie who is the sufferer, should we really approve of his behaviour? After all, Pan, not one to be gripped by misplaced vanity, was able to think “whether she realised that the make-up improved her, as it certainly did, in spite of what Guy had said.”

Later, after the make-up has been violently removed, she comments, “She looked no longer like an American film star, but merely Marjorie Manners of the Fourth Form at school.”

But why shouldn’t poor Marjorie want to try things out? Why shouldn’t she indulge her dreams? It’s the way of the world and relatively harmless compared to the other things she gets up to. Pan’s reflections about Marjorie’s epic battles with Guy now strike me as being both sad and unconsciously ironic.

I wondered why she would persist in fighting with Guy. Since he was physically so much the stronger, besides being terribly determined, she always came off worst in the encounters. Yet she refused to own herself beaten. It was beyond me!

It was also beyond me as well when I first read it. But Marjorie has spirit and zest and go and, what is more important, some sense of her own identity. She may be wrong but Guy is simply insufferable and I could cry tears of mortification alongside his victim that night. As for Pan I realise that she has a long way to go before she develops any sense of self-esteem. Lorna Hill succeeds in drawing me to her again as I recognise all too clearly the child I once was.

Let me be totally honest, however, though I felt like Pan and could even relish the liveliness of Marjorie, I always wanted to be Esme. And so did Pan. Just look at the opening of Chapter 9 as Pan watches Guy and Esme going into Beadnell for an evening at the picture show:

Peter and I watched them go, and I thought of the admiring glances there would be from passers-by as they rode along: Guy, tall and sunburnt, with his dark hair and level grey eyes, astride his dashing black pony; Esme on her tawny chestnut, with her corn-coloured plaits flying, and her sweet sensitive little face looking up at Guy as if he were a god.

How like Pan to acknowledge the superior attractiveness of her friend! How like Pan to be filled with yearning rather than resentment.

“It must be nice to be as good-looking as that,” I sighed half under my breath.

“What’s that?” asked Peter.

“Oh, nothing – at least nothing you’d understand.”

No, I thought, only a hopelessly plain girl with freckles and a snub nose and mousy hair would understand the awful longing to be as lovely as Esme and Marjorie were.

That’s the clever trick that Lorna Hill pulls off and which still works for me even today. We can understand and sympathise with Pan and yet not feel annoyed about Esme, who is totally unconscious of her own physical charms. We also, I am sure, now realise that Pan is totally wrong when he says “Marjorie was the lucky one, for she knew perfectly well how pretty she was, so she enjoyed knowing it.”

What Pan needed was a little bit of Esme’s lack of concern about her appearance and a lot more of Marjorie’s self-confidence without the mile-wide wilful streak. But then she wouldn’t be Pan and I wouldn’t feel for her so much.

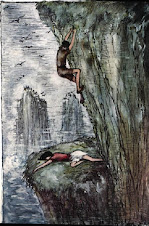

Wow! I’ve just realised that during the course of Stolen Holiday Guy manages to hold each of the girls in his arms. He’s always a perfect gentleman, of course, but this must have been part of the thrill of the book when I first read it. They are three memorable occasions and Guy is really like a hero at each crisis. There, I am allowing him to slip back into my heart again. Still, better to tell the truth and get it over with.

Pan’s attempted moonlight (actually the moon doesn’t shine) swim ends up with her being confused in the darkness and actually setting off dangerously into further depths rather than making her way back to shore. Guy comes to the rescue and then, seeing her shaking with cold… “He picked me up altogether, completely ignoring my expostulations, and carried me into the bungalow.”

Before he found her she had swallowed lots of salt water and has to be sick. Thus it’s a typically un-romantic episode for Pan. She feels a complete fool but is grateful to Guy who doesn’t reveal the truth about her misery to the others.

Marjorie’s cliff accident also brings out the best in him. In fact he can’t really be faulted. He performs the difficult climb, he nearly exhausts himself carrying her out, he rallies the others to help get her warm and finally he lavishes care and affection on the very girl who has spent most of her time confronting him and arguing with his every instruction:

…and Guy sat down near the fire and took Marjorie in his arms again, blankets and all. At the same time he talked the most utter nonsense to her, but it seemed to cheer her up no end, and after a bit she really did get warmer, and Guy fed her like a baby with toast dripped in strong sugary tea.

I can’t fault him. I don’t want to fault him. But it is with Esme that he is at his best. I always think of it as the cornfield episode. Guy realises that Esme is about to witness the wholesale slaughter of all animals left as the last few stalks are cut down as part of the harvest. A particularly bloodthirsty boy waiting for his chance to kill makes the whole scenario potentially revolting. Guy seizes Esme and carries her away from the field and down to the shore, where the roaring waves are breaking. He is determined she will neither hear nor see the outbreak of the savagery. He takes her on his lap and tries to talk her out of her anger and grief…

“Darling,” he said earnestly—and I have never before or since heard him use the word to any of us—“you couldn’t have done any good there. You couldn’t go hitting those large men over the heads with your little bare hands, now could you? Or throw yourself into the reaper, or in front of their guns, as you were thinking of doing? Oh, yes, I know you were, so you needn’t bother to deny it!”

There then follows a long attempt to reconcile Esme to what happens and to talk about the ways in which it can be stopped in the future. Guy, contrary to all his strict code of honesty and plain speaking, even produces a white lie in order to comfort her. Pan’s thoughts are echoed by the reader.

But such as it was, I don’t think he would be held guilty of that lie in Heaven!

I don’t have the book available (Roll on those reprints!) but I seem to remember a similar situation in Border Peel where Guy resumes his old border feud between the Charltons and the Fenwicks largely because Ralph Fenwick commits a similar spree of killing creatures in front of Esme and Pan.

In spite of my good intentions I don’t seem to have written much about the glorious descriptions of Beadnell, Dunstanburgh, Bamburgh and the Farne Islands that are peppered throughout this book. Even the evening spent at the little fun-fair sticks firmly in my mind, though I wonder at myself for taking so much satisfaction in the fact that Marjorie manages to get Guy thoroughly riled by using her feminine charms to get endless free rides on a roundabout out of a local youth.

Compared with Marjorie and Co. our favourite villainess has been remarkably restrained in this book. She even goes so far as to submit meekly to taking swimming lessons from a helpful Guy. However, the dramatic ending more than makes up for the comparative ‘civilised’ behaviour that she has shown so far. It is the idea of a ‘Queen of the Harvest’ that precipitates the drama. I note with approval that Guy tries to make Pan feel good about herself: “You know there are more qualities that a queen must have than just mere good looks, Marjorie, and it strikes me that Pan would make as good a queen as anyone.”

He follows this up by saying that she is a “nice kid.” Marjorie on the other hand is anything but nice and any self-control that she may have had snaps when she sees Esme, already promoted above her as monarch of the harvest, about to be granted the privilege of riding Guy’s wonderful horse, Flyaway. Her nails come out like the claws of a wild animal and she scores a mark down both of Esme’s cheeks. Guy’s tenderness to his favourite is matched only by the ferocity that he manifests towards Marjorie. She only escapes a beating by a riding crop because she has run away home.

It is with mixed feelings that I read the epilogue to the story. Yes, I wanted Marjorie to be punished, but no I don’t want her drummed out of the Clan. Even Guy has to admit that he feels a bit of a ‘cad’ after the ceremony of expulsion is completed. He hasn’t quite forgiven her but he is beginning to feel for sorry for her.

In view of all her behaviour so far, it really is remarkable that by the time we get to Castle in Northumbria Guy’s understanding of Marjorie has extended even further. All the children are a little older and, as well as giving me a clear picture of how each one behaves, I find that Lorna Hill is gradually revealing the backgrounds that have helped to shape each one of the girls’ personalities.

When Marjorie learns that she can’t come away on the camping holiday with the rest of the Clan, quite a few of the details of her home life come tumbling out. She complains about her parents:

“Well, I don’t see a great deal of my father,” Guy said quietly.

“But he’s there behind you, all the same. You know that if you wanted him, he’d come like a shot,” Marjorie told him bitterly. “And Pan’s father reads aloud to her, and I’ll bet Esme never goes to bed without her mother comes and says goodnight—or Pan, either. I don’t see my mother from one weekend to the next. If she does happen to come in before I go to bed, all she says is: “What, not in bed yet, Marjorie?”

The others all realise how well off they are. By the end of the book, of course, Marjorie has behaved worse than ever. My word, I nearly said “wonderfully worse than ever” because she injects such life into the proceedings. The moment when she throws the white dress in the air and slashes at with the knife is simply tremendous. She’s also been beaten for the first time. Guy has finally carried out his threat. It’s what comes after that always worries me. Marjorie is actually shown to have improved in her behaviour because of the beating. In the end she is even prepared to shake hands with Guy:

“I thought I detested you,” Marjorie was saying. “But I find I don’t after all. You’re really quite decent—on and off. So I don’t mind shaking hands with you, if you really want me to.”

It really is too good to be true. Can this be Marjorie? Castle in Northumbria has the happy ending to beat all happy endings. It feels more like the ending of the series but Marjorie and the gang all return for No Medals for Guy.

In between he has two adventures with the other lot—I mean the boys and girls in the ‘Patience’ books. In So Guy Came Too he rescues the whole holiday by his practical and positive approach to running a camp. Once again he gets his way in each of his encounters with the erring females. They are always in the wrong—wanting to swim in a dangerous tarn, wanting to go to a village dance with a perfect stranger. At times you can see that they are rebelling because they find his manner so imperious. His solutions to these problems always work. The girls always end up feeling a strange mixture of both humiliation and gratitude.

I gave another sigh of relief. It was wonderful to think that there was someone upon whose broad shoulders I could lay my burden. I even began to think there was something marvellously comforting about Guy, after all—even if he was a little high-handed upon occasions.

Once again, however, I must admit that I find some of his attitudes annoyingly old-fashioned. In fact, as I read these ‘Patience’ books again, I find myself feeling a little ashamed of my sex. Judy and Elizabeth are always in the wrong and Guy is always so frustratingly right. On the one occasion when he puts his foot in it and accuses Judy of being to blame for Patience being stranded out on a rock off the coast, his reaction when he discovers his mistake is so instinctively frank and honest that again events are turned in his favour:

Then he looked across at me and added earnestly: “I’m terribly sorry, Judy. It’s I who deserve to be beaten—not you. Please forgive me.”

I said nothing. My pride had been badly hurt, and my anger against Guy for his harsh words was still too fresh for me to be able to forgive him on the spot. Evidently he understood how I felt, for he said nothing more.

Do you see what I mean? He’s at fault but Judy is the one that is made to look mean and petty. His noble nature is proved again a few seconds later when he forgives Patience for all the trouble she caused. But what about Judy’s proposed entry into the Bathing Beauty Competition? For him “It’s not decent” and his is the only opinion that matters. Once again he enforces his will and once again she ends up grateful. I begin to ache for him to show a little more vulnerability, to be a little less than perfect.

I was never as happy with No Medals for Guy as with the rest of the ‘Marjorie’ books. Before I turned the pages once more my memory seemed only to contain two facts: Guy rescues a boy and girl from drowning and Guy saves a woman from a fire in a mansion. It goes without saying that he does all this with a minimum of fuss. By this time I wouldn’t expect anything else; it has become merely routine. I really wanted to know what had happened to Marjorie? Has her membership of the Clan offered her a friendship that can replace the obviously missing parental love and concern? Will it help her make the most of the best things in her nature? Has Pan overcome her self-loathing, mollified by Guy’s apt comment on her being a “peace-maker” and therefore likely to be “blessed”? Has Esme grown a tougher shell that will protect her from all the harshness of the world, particularly the inevitable cruelty that will arise in our treatment of animals? It now seemed strange that I had started this re-examination of the books with a desire to go through those happy days again in the company of Guy and all his sterling qualities. Now I was much more interested in the fate of the girls. There are only hints. As an adult reader I can see that Lorna Hill is cleverly indicating that each of them has a long way to go.

First there is Pan. Her troubles are by no means over. She has nothing, she feels, to recommend her to anyone and her frustration in this last adventure shows itself in the form of cutting and sarcastic remarks. Peter, her twin brother, comes in for more than his fair share of her shrewishness. Guy is used as the catalyst for another painful round of self-examination:

Guy strode away, and I watched him go with a sigh. He was so splendid and so sure of himself and all he did, that I felt he would never be able to understand what it was like to be a plain girl with mousy hair and freckles and a snub nose, and only a sharp tongue to make people take notice of her.

Marjorie is still full of mean and petty little tricks but somehow I miss the largeness of her villainy that led to the appalling incident where she scratched Esme’s face in Stolen Holiday. I also miss those glimpses we have into her basic unhappiness that explained her behaviour in Castle in Northumbria. The final picture that lingers in my mind is of the self-confident and beautiful girl who strides down the catwalk in the mannequin parade in the shop in Morpeth. Already, one feels, Marjorie knows the ways of the world and how to use her very obvious charms in order to make her way in it.

Esme has a different kind of beauty that is well celebrated in the same show. Once again we rely upon the generous-hearted Pan to give us a clear picture of something terrifically appealing:

She hadn’t any make-up on at all, and she didn’t look the least bit glamorous. She looked—well, I can’t describe the look exactly, I only know that I’d have given anything in the world to look as Esme did then, her blue eyes shining with excitement, and that sweet shy expression on her face.

Thank goodness, however, that Esme does not get caught up in any feelings of vanity. She desperately wants to win Guy’s approval and makes up her mind that she will earn some money by “the sweat of her brow.” She even runs away from them all in order to do so.

This brings about another crisis in the affairs of the clan and, for once, it is Peter, who says openly what everybody had unconsciously realised but had never thought of saying aloud:

“W-aal!” drawled Peter. “What d’yer know! I always said you spoiled that kid, Guy. She leads you by the nose!”

Guy’s brows drew together.

“What do you mean?” he said stiffly.

“Oh, come off it!” Peter laughed. “You jolly well know she does.”

We stood staring at Guy, too surprised to say anything. The very idea of anybody leading Guy by the nose was queer, but that Esme, the littlest and gentlest of us, should be the one to do it was queerer still. Yet we knew what Peter said was perfectly true; and we guessed from Guy’s expression that he knew it too.

And that explains Jane.

“Jane—who’s Jane?” you may well ask.

Stop reading now if you have never read the ‘Wells’ stories by Lorna Hill.

Jane becomes Guy’s wife, the mother of his children and lives with him in Horden Castle.

But what happened to Esme? We are never told. You can speculate as much as you like—a final quarrel with Guy about the iniquities of hunting, perhaps? I have one or two friends who used to get quite irate about the disappearance of Esme. After all even Marjorie and Patience and Richard and Elizabeth are spared to play their parts in the panoply of events that are unfolded in the 14 ‘Wells’ books. Their characters are different. It would be almost impossible to preserve that essential quality of innocent girlishness, of artless kittenish beauty, of tender-hearted recklessness that makes her such charming company in the ‘Marjorie’ stories. And so we get the second-best thing in Jane and other reflections of her in aspects of Mariella and of Sylvia and perhaps, most of all in Vicki and Patience.

Guy stays the same. His protectiveness towards Jane in her youth mirrors his treatment of Esme, Pan, Judy, Patience and Elizabeth. He deals with the appalling Fiona and nasty Nigel in just as effective a manner as his more youthful self put down Ralph Fenwick and Sylvia Wade. Yet he is powerless in the face of the love that he starts to feel for Jane in Jane Leaves the Wells. I can like him so much more thoroughly when I see him at her mercy, brave enough to be open in his feelings and dignified in his apparent defeat. He is no longer in control of events. Both gentle and masterful treatment of Jane can lead her back to loving horses and re-assuming the mantle of a Northumbrian but they can’t compel her to give up her career. Guy has got to accept his fate just like the rest of us. Lorna Hill permits him his time of unhappiness, short though it may be. He can’t even bear to watch Jane in her performance on the television. He is no longer too proud to accept the sympathy of others for he realises that Mariella knows all to well how he is feeling. In short, he suffers and I like him for it. I have no time for those women who think Jane ought to have stuck with ballet and that it is an unhappy ending that she can’t remain as dedicated as Veronica. After all Veronica’s selfless or is it selfish dedication succeeds in making her own daughter pretty unhappy. Those who believe that Lorna Hill placed the values of art and the ballet above the joys and the pains of human love are talking balderdash. People came first with her—unless they were people who mistreated animals.

I must admit that I can’t like the ‘Wells’ stories as much as the ‘Marjorie’ or the ‘Patience’ ones. I used to think it was because I couldn’t bear the thought of losing Guy to another woman. Now I understand that it’s the girls I miss. A thorough and prolonged study of Marjorie growing to adulthood would have been fascinating. I know I would have redeemed her by love but not until she had got into (and out of) the most frightful scrapes. Most of all I wanted to know what happened to Pan for it seems to me she is more like me than any of the others. The nearest I am going to come to any feeling of ‘closure’, as the Americans call it, is to remember that other rather downtrodden and self-deprecating character, Mandy, with the more beautiful elder sister, and to recall what happens at the end of The Vicarage Children on Skye where the truth about her future finally begins to dawn.

As I said earlier, I managed to track down most of the ‘Marjorie’ and ‘Patience’ books but Border Peel eluded me. I look forward to adding it to my collection. I have also just learned that Northern Lights, a missing story from the ‘Marjorie’ series has been published. By hook or by crook I mean to find a copy. After all I still need to know whether my infuriatingly ‘perfect’ hero behaved as he usually did. And in that way I can find and lose him all over again. That really is the magic of a good story or, in the case of Lorna Hill, of a good set of stories.

About the author

Born in Whitley Bay in 1946, Philippa Morley attended Newcastle Central Girls' High School, studied French and Spanish at Newcastle University in the 1960s, worked for Marks and Spencer on their graduate scheme for 8 years, met and married her husband, Edward, and subsequently lived in Hong Kong until it was handed back to the Chinese. In recent years she has been rediscovering the childhood books about her own home county Northumberland, in particular those by Lorna Hill and Winifred Finlay. She has two children and one grand-daughter.

A Hero Lost and a Hero Found

by

Philippa Morley

“Hurrah!” I shouted in the best pony story fashion. “This is simply the most super news I’ve heard in years.”

My husband retreated further behind his newspaper as though he could hide from the wonderful discovery I’d just come across in Charlotte’s letter. Somehow he thinks that The Times and a stoical silence will keep me from telling him even the most vital snippets of information.

“They’re reprinting the ‘Marjorie’ and ‘Patience’ stories by Lorna Hill. I’ll be able to collect them and read them all over again.”

Silence.

“Did you hear, Edward. They’re reprinting Lorna Hill’s stories. You remember how upset I was when I learned mother had given them all away to a jumble sale whilst we were out in Hong Kong.”

“Really, dear, that’s very nice.”

Honestly, what did I expect after 35 years of marriage? Something more than “nice” I suppose. The more I thought about it, the more I realised that I wanted more from him than I could reasonably hope to receive. The problem was that Edward just wasn’t like Guy. All my life I had been hoping to meet someone like Guy.

Guy? Guy Charlton, of course—the clear hero of the ‘Marjorie’ books and sometimes hero of the ‘Patience’ stories. Why Guy was indispensable to me when I was growing up in Newcastle Upon Tyne in the 1950s and 1960s! You see I expected to meet him around every corner. I would be walking down from the girls’ Central High School and he would be in town from Horden Castle and we would bump into each other at the top of Northumberland Street, just where it turns into the Haymarket. My parcels (why I was carrying parcels I can never explain) would fall to the floor and he would rescue me, apologising even though it had mostly been my fault. And that would be the start.

Pretty soon I would be on holiday with him and the others in the depths of the Northumberland countryside or on some remote beach near Bamburgh Castle. I conveniently ignored the fact that Lorna Hill had decided on a very different destiny for her favourite young man and had myself married off to him. I can vividly remember riding down an avenue of tall trees lined by all the characters from the books with swords upraised over our heads in salute, as our carriage, driven by Guy himself with masterly control, headed off into the sunset. My favourite pony, Border Thunderer, would be waiting in Horden Castle for us to get back from our honeymoon…

Well, I married Edward instead and spent thirty years staring at the outside pages of The Times across the breakfast table.

But, enough of that.

Charlotte’s letter had made me determined to revisit the stories of my youth and meet again the object of my schoolgirl dreams and desires. It would take too much patience to wait for the whole series to be reprinted. Now that the idea was in my mind I had to have the books.

Well, I had no idea that they would prove so difficult to obtain! Just one turned up in a second-hand book-shop in my local area. A friend persuaded me to go on the Internet and by paying through the nose, I managed to collect a further six volumes, some with dust-covers and some without. I could have had any number of ‘Sadler’s Wells’ stories but my friend, Lucy, has a full collection of those and I knew I could borrow any of the fourteen ballet stories, plus a few ‘Dancer’ adventures if I really got the Lorna Hill bug.

With some trepidation, therefore, forty years later, I opened the copy of Marjorie and Co. and began to read. This, I suppose, is where this article really starts and so I apologise for all the waffle so far. However, these books had meant such a lot to me and I feel you need to know that I am not exactly a detached critic when I make the observations which follow.

I don’t know about you but when I was reading books as a young girl and as a teenager I used to skip the little introductions and the ‘forewords’ and ‘prefaces’. “Just get on with the story” was my motto. A lifetime of scanning the small print and sad experiences with missing vital instructions on household appliances has taught me to be a little more patient and circumspect. Now I read everything. And so I read the Foreword to Marjorie and Co. and that’s when I received my first shock. Writing in the first person character of Pan, Lorna Hill actually opens the first book by describing the faults of each of the characters.

“Guy is distinctly bossy, Toby is what the grown-ups would call ‘a bit on the stolid side,’ Esme hasn’t the ghost of a sense of humour, whilst I’ve got oceans of faults.”

So “Guy is distinctly bossy”. Well, that’s just Pan’s opinion, isn’t it? Obviously one of her “oceans of faults” is the inability to see Guy as he really is. Honestly, you would think she would know better than to criticise him for one of his virtues. I mean Guy is just so masterful. There’s nothing namby-pamby about him. As for those girls, I had never understood what he could see in them. But, even as these thoughts were crossing my mind, I realised that I was being unfair. Then, as a twelve year old girl, Pan, Esme and Marjorie had been like rivals for the hand of my hero—now I have seen my first grandchild arrive in the world, and I gaze at life from the wrong side of fifty, I really ought to know a little better. After my first ‘new’ reading of Marjorie and Co. my thoughts had undergone a glorious revolution that I should like to share with you. The tiresome girls that got between me and the lovely Guy were transformed into my best friends and, as I began to understand with mounting appreciation, that they were, in fact, reflections of different aspects of my own character. It was in fact the ‘hidden me’ that I had never wanted to acknowledge, those uncertain thoughts and feelings that eventually shape us into the people we become. More marvellous even than the people were the countryside and the towns where all the stories were set—in those days they were simply “the places where exciting things happened.” Now they are my only route to the past, unless I accept the challenge of writing a very dull autobiography of my early years in the North-East. Even then I still wouldn’t have the gift of a Lorna Hill.

As early as the first chapter of the first book I began to get these feelings. Poor Esme and Pan have to make a “courtesy visit” to have tea with Marjorie Manners, a girl who lives in their neighbourhood but who also goes to their boarding school. They already know her well and heartily dislike her. Back then what parents said was law. Pan tries every argument she can think of but is met with her mother’s implacable resolve:

“Well, I’m afraid you’ll have to go and have tea with her,” insisted Mummy firmly, cutting me short.

Oh, those “visits”—with what pain I can still remember them! Mine were mostly to elderly relations in other districts of respectable surburbia in Newcastle. They normally took place on a Sunday and only those that have lived through the dullness and oppression of spirit caused by a 1950s Sunday afternoon and evening can fully appreciate the depth of my feelings.

However, let us be fair. The first chapter of Marjorie and Co. makes it clear that children both then and now seem to have that specially programmed capacity to wreak a peculiar form of revenge for being brought into the world in the first place. As Pan and Esme beg and beg for ponies to ride and fill every letter home from school with unceasing ‘horsy’ information, so I am reminded of my marathon nagging sessions which eventually reduced my mother to frustrated acquiescence in my latest fad. Yes, let us try to dispense justice to both sides in the never-ending war between the generations. As I look back to the freedom enjoyed by the girls in this story with the benefit of thirty odd years hindsight I realise that they and I were living in a literary ‘make believe’ land. However, whilst the implausibility of several of the plots now makes itself clearly apparent, I can recognise a deeper truth in some of the behaviour that I never noticed before.

Take Marjorie, for instance. She is meant to be the villain of the piece and we can soon understand the dread that fills Esme and Pan as they draw near to Windynooks, the Manners’ opulent house. However, we are not treated to Marjorie ‘swanking’ over the tea-table whilst Pan and Esme feel like poor relations. That’s much too tame for Marjorie.

Marjorie never arrived decently—she always burst, or sprang, or flung herself. She was riding bareback, and I suppose she did look rather striking in her jodphurs and scarlet sweater—she often wore scarlet. I think she knew that it suited her dark prettiness—not to mention her disposition!

I ask you honestly, “Who would you rather be—Esme tumbled in an undignified manner into a holly bush, Pan sitting bolt-upright on her little cart-house of a pony or Marjorie arriving with dramatic effect and admired by her contemporaries for her attractive appearance?”

However, neither Pan nor Esme is lacking in spirit and they show this on the first encounter. As Marjorie shows off her new swivel manger and declares “No fear of flashing heels and snapping teeth,” Esme traces the smart remark to an advertisement in Horse and Hound and says she thinks the manger would be jolly useful for pigs. Pan manages to get in her own deflationary remark about new saddles being so stiff and horrid. The chapter ends with Pan confessing that “Really, Marjorie brings out all the worst in me!”

All her carefully cultivated attempts at politeness to her hostess have been forgotten but, nowadays, I soon recognised that, of course, Marjorie has been put into the stories to bring the best out of everybody and this includes my lovely Guy.

Chapter Two is a catalogue of Marjorie’s sins. She really does behave appallingly. In a race with Esme she sets off before the word “Go” and later hits poor Willow with her riding crop just in case there was a chance of being beaten by a rival mount. Naturally Willow, with an inexperienced rider, sets off at a frantic speed towards a nearby wall. Disaster lies ahead for Esme. It’s time for the hero to make his presence known. Like Marjorie, Guy can never arrive tamely on the scene and he performs the fairy-tale prince act with skill and panache. Already Esme has lost her heart to him and Marjorie is ready to take him on as a serious opponent. Everything she tries, including further cheating and attempts to hit him with a riding crop, is doomed to failure in the face of his imperturbable will. I used to relish his victory in this first encounter but now I am not so sure. It comes a little too easily and is a little too absolute. Black and white is no longer so attractive to me in literature as the more subtle shades of grey. However, Lorna Hill doesn’t let me down and I read with astonishment a passage that had entirely eluded my memory. Yes, yes—I had taken in the information before but I had never really followed the flow of the narrator’s emotions so closely. It concerns Pan and how she came to get her name:

“You see,” I went on, determined to get it all off my chest, “it was a filthy woman—I mean a mouldy woman, a poetical friend of Mummy’s when Peter and I were born. Peter’s my twin brother, by the way. She—the woman, I mean—raved like everything about Peter Pan, and got Mummy to call us that? One Peter and the other Pan-sy. Awful, wasn’t it? Of course Peter was all right, but there was I, dubbed Pansy for evermore!”

For Pan it is a cruel joke that she doesn’t look like anything that could have the remotest claim to beauty and certainly not a flower “unless it’s a spotted orchid, or something that’s got freckles! I’m not even a common or garden dandelion.”

No amount of kind words from Esme or gruff common sense from Guy can take the edge off this sad confession of the lack of self-worth that Pan feels about herself. And that’s what cut me to the heart, for, much as I had always wanted to be the sweet and pretty Esme or the lively and spirited Marjorie, I realise now I was in fact more often the faltering and miserable Pan.

So, as I read all the ‘Marjorie’ books that I could lay my hands on for the first time in donkeys’ years, I began to develop an extra special relationship with this least likely of heroines. After all she was a splendid comic narrator and her frustrations with the inadequacies of the English language caught exactly my own feelings about the way in which words have to be carefully watched or they take on a life of their own. Take, for instance, that day that she discovers Otis Island. Pan is left on her own and begins to explain why her friends are not available. She reaches Esme:

Esme had been hauled off to the dentist’s, so she was a dead loss, because nobody, however hard they try, can concentrate on anything but the job in hand—I should say the job in the mouth!—when they are at the dentists!

Best friend or not, on the same day Esme comes in for her fair share of teasing. We can appreciate again Pan’s way with words and the choice of the apt simile:

“Well, now, can we have our council of war?” asked Esme in an injured tone. “You do make a fuss about unimportant things!”

Guy turned and looked at her sternly.

“Another word from you, my child, and I’ll—I’ll—I’m dashed if I know what I’ll do to you.”

“Wash the tidemark off her neck!” I suggested wickedly.

Poor Esme flushed crimson.

“Pan! Don’t be hateful!”

“Well, you know you have one—a huge one! It’s like Roker sands on a Saturday night, after the trippers have gone home... Ouch! Let me go, you beast!”

The attack on Pan comes from Guy and he tells her off for making personal remarks. It’s funny that I hadn’t noticed quite how often he steps in to be protective towards Esme. He enjoys teasing her himself but he won’t let anyone else do it. Yet, as I read Pan’s splendid description of her journey down the river after Miss Otis, her mischievous cat, and saw how she faced up to Guy and his anger, I began to feel more and more sympathy with the girl that I had always regarded as the nonentity of the group.

Gosh, isn’t Marjorie awful? I had forgotten at least two thirds of the things she did. Who could like a girl who cheats in races, makes constant sneering remarks, burns their gymkhana fences, saws holes in the bottom of their boat, covers their horses with tar and sprinkles their picnic sandwiches with paraffin? How could they let a girl like Marjorie into the clan that they had formed. The first time I read the book I couldn’t believe it. I remember thinking how noble it was of Guy to change his mind and to let her join. Here’s the key moment:

Then suddenly he changed the subject abruptly, and looked Marjorie straight between the eyes: “Why don’t you try being decent?” he asked her. “You could, if you set your mind to it. You’ve got loads of ‘go’ and pluck, and as for determination—whew!” He whistled.

I know that I ought to have appreciated this as a genuine example of Christianity, the parable of the lost sheep brought into the fold, but I was probably too busy simpering over Guy whilst at the same time thinking how lively the story could now become. This time through I was struck by Pan’s shrewd observation “…I, for one, had grave doubts as to the wisdom of Guy’s idea of admitting Marjorie into the Clan. He still didn’t know her as well as I did.”

Well, of course, Pan is right and Guy is wrong. It’s all very well thinking of those who go astray but Marjorie proves to be totally incorrigible. Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t have her any other way—the stories demand that she must be so. It’s just that the wisdom I have gained along with my grey hairs tells me that it’s not right that she should be allowed to cause such mayhem and suffering. When I think of what she does to Esme…

But back to Guy. Once I used to admire how grown-up he was and wonder how he could put up with the others so less experienced and less talented than himself. Now I feel like I am going through the books with a “smug” detector and finding that it is constantly setting off alarms:

“Gosh! You are a lot of kids, aren’t you?” he exclaimed. “I’m such a lot older—”

“Kids!” Marjorie retorted. “We’re nearly as old as you, let me tell you!”

“Not quite! I’m nearly fifteen,” laughed Guy. “Anyway, I didn’t mean in years; I meant in experience. So far, you’ve never done anything in your lives but play. Always some grown-up or other at the back, putting up picnic things for you, slicing the bread for fear you cut your fingers, giving you milk in a bottle, tea in a thermos – making things easy for you. I’ll bet you’ve never slept outside….”

But he is kind and, even in the first book, it is not just to the pretty and tender-hearted Esme. When Pan learns that her pony Billy is likely to be sold it is Guy that forces the truth out of her. It would have been so much easier for him to have treated her like the silly girl she was when she tried to overfeed the poor animal, and to have walked away from the disturbing outflow of feminine emotion.

Yes, he is as firm as a rock when it comes to any trouble but he is also disturbingly rigid when it comes to controlling the girls’ behaviour. I mean they are not really allowed to think for themselves and I sometimes believe it would be possible to accuse him of having double-standards. Take what happens at the circus. Marjorie seizes the opportunity to take part in a talent competition and wins half-crown. Guy is furious and hands back the money to the ringmaster. Later he attempts to tell her off:

“You only made yourself cheap tonight, Marjorie. You should have heard what the lads behind us were saying about you!”

“What were they saying?” Marjorie demanded eagerly.

“Never mind,” answered Guy severely.

“Oh, you’re old-fashioned—starchy!”

“Perhaps I am old-fashioned,” he admitted. “Anyway, those are my views. Take them or leave them!”

“I’ll leave them, then!” Marjorie said pertly.

“No, you won’t! You’ll jolly well take them, while I’m in charge of you.”

He insists that she scrub herself clean with carbolic soap so that Esme and Pan will not catch anything from the dirty sawdust and the soiled costume she wore. Then he calmly informs them all that he is taking part in the circus the following night in order to pay for the mistreated monkey that has caught Esme’s sympathy. At once Marjorie is there:

Suddenly there was a terrific whiff of carbolic, and Marjorie sprang into out midst, her eyes sparkling.

“Now who’s making exhibitions. Now who’s making himself cheap?”

“I’m not a girl, my good kid!” said Guy indignantly. “Anyway, I’m not just showing off. At least I’m doing it for a purpose.”

It’s just no good. Whatever his purpose, those first words “I’m not a girl...” make the hackles rise. I can tell myself with conviction that it is not hypocrisy on Guy’s part, that he genuinely believes that girls must behave differently, according to his pre-set ideas, but I still don’t like his certainty about his own rightness. I like him better some pages later when Pan realises that he has lost his temper with Claudine, the obnoxious little girl who has run away to their camp. I am even happier when I discover that the reason for his uncharacteristic loss of his temper is his affection for Esme. She has been slapped in the face by Claudine but has refused to sneak on her. Yes, as I read the books again I became quite reconciled to the fact that Guy’s affection for Esme considerably outdistanced his feelings towards anyone else. That’s what made it all the more upsetting when … But I’m getting ahead of myself, as Pan would say in one of her narratives, for I want to look next at Stolen Holiday.

Ah, Northumberland! If you have never been there, then you must go. It used to thrill me when I realised that I had been born in the same county as my hero. Even years later I used to ask my mother whether we had any relations who belonged to the Charlton family—no, not the illustrious footballing brothers who came from Ashington to represent England in our tremendous victory in the football World Cup. It was the wild borderers of the Middle Marches that I wanted to find amongst my distant kinfolk. The kinship must be distant, you realise, there must be no bar to our eventual nuptials. A girl can dream, can’t she?

You must go to Bamburgh Castle. Only then can you appreciate what Guy says as the superb Stolen Holiday begins:

Guy broke the silence.

“It’s queer,” he said slowly, “how this place gets hold of you! I’ve lived in Canada all my life, yet somehow it never seemed home like this does.”

Now I realise how clever Lorna Hill was in the way she created the background of her leading man. That Canadian upbringing gave her a rich vein of interesting differences for her to tap into as she developed more and more stories. Every aspect of the outdoor life was shown to be well within his compass. He can ride, he can swim, he can handle a boat, he can climb, he can run a camp—and he can do all of these things much better than his English contemporaries. He is tall, he is tanned and the contrast between his grey eyes and his dark hair makes him look even more striking. Moreover his manners are distinctly un-English. He has lived amongst French Canadians and not for him is the standoffish reserve of the English schoolboy of fifteen. Pan contrasts the shyness of Esme, Marjorie and herself with Guy’s lack of inhibitions.

We were all a bit shy, I think. Esme was distinctly pink, but Guy himself was perfectly natural and self-possessed. He swung Esme right off her feet and kissed her—he hadn’t nearly the same aversion towards kissing that we had.

What I would have given to be a member of the Clan at that moment waiting in turn to be greeted. But then I remember that he is really a bit of a dictator and will brook no arguments with his leadership. For him right is right and wrong is wrong and girls will not be allowed to behave badly and escape punishment just because they are girls. But should he be allowed to smack any of them—even the ghastly Marjorie? Really, it’s no good wondering whether he is right or wrong to do this, Guy will behave according to his interpretation of morality whatever I say or think. That is a part of the problem I now find with Guy. Surely it must be impossible to live with someone who is always right. It’s even worse being with someone who lets no error pass unchallenged. There’s always a time for keeping quiet, for letting people grow into a realisation of their own errors. And, anyway, is he always right? Let’s take the issue of teenage girls wearing make-up, for example. Naturally, it’s Marjorie who puts Guy to the test—who else would it be?

When she came out on to the veranda I thought there was something different about her, but I couldn’t think for the moment what it was. She looked extraordinarily pretty; her cheeks glowed, her eyes seemed even bigger and more melting than ever, her eyelashes were positively sweeping.

Guy is certainly entitled to his opinion and by now we know for sure that he is going to express it:

“Made-up?” he said contemptuously. “I thought that in England, at least, I wouldn’t see kids of thirteen with painted faces! You were quite a decent-looking girl before you put on all that filthy stuff. Now you look fit for nothing but a circus! Go and wash it off at once!”

Do you think he should have scrubbed her face with sponge and carbolic soap? Do you honestly believe he should have used Vim! I mean, have you felt Vim on your skin?

Just because it is the obnoxious Marjorie who is the sufferer, should we really approve of his behaviour? After all, Pan, not one to be gripped by misplaced vanity, was able to think “whether she realised that the make-up improved her, as it certainly did, in spite of what Guy had said.”

Later, after the make-up has been violently removed, she comments, “She looked no longer like an American film star, but merely Marjorie Manners of the Fourth Form at school.”

But why shouldn’t poor Marjorie want to try things out? Why shouldn’t she indulge her dreams? It’s the way of the world and relatively harmless compared to the other things she gets up to. Pan’s reflections about Marjorie’s epic battles with Guy now strike me as being both sad and unconsciously ironic.

I wondered why she would persist in fighting with Guy. Since he was physically so much the stronger, besides being terribly determined, she always came off worst in the encounters. Yet she refused to own herself beaten. It was beyond me!